Das Projekt

Von Roland Brockmann

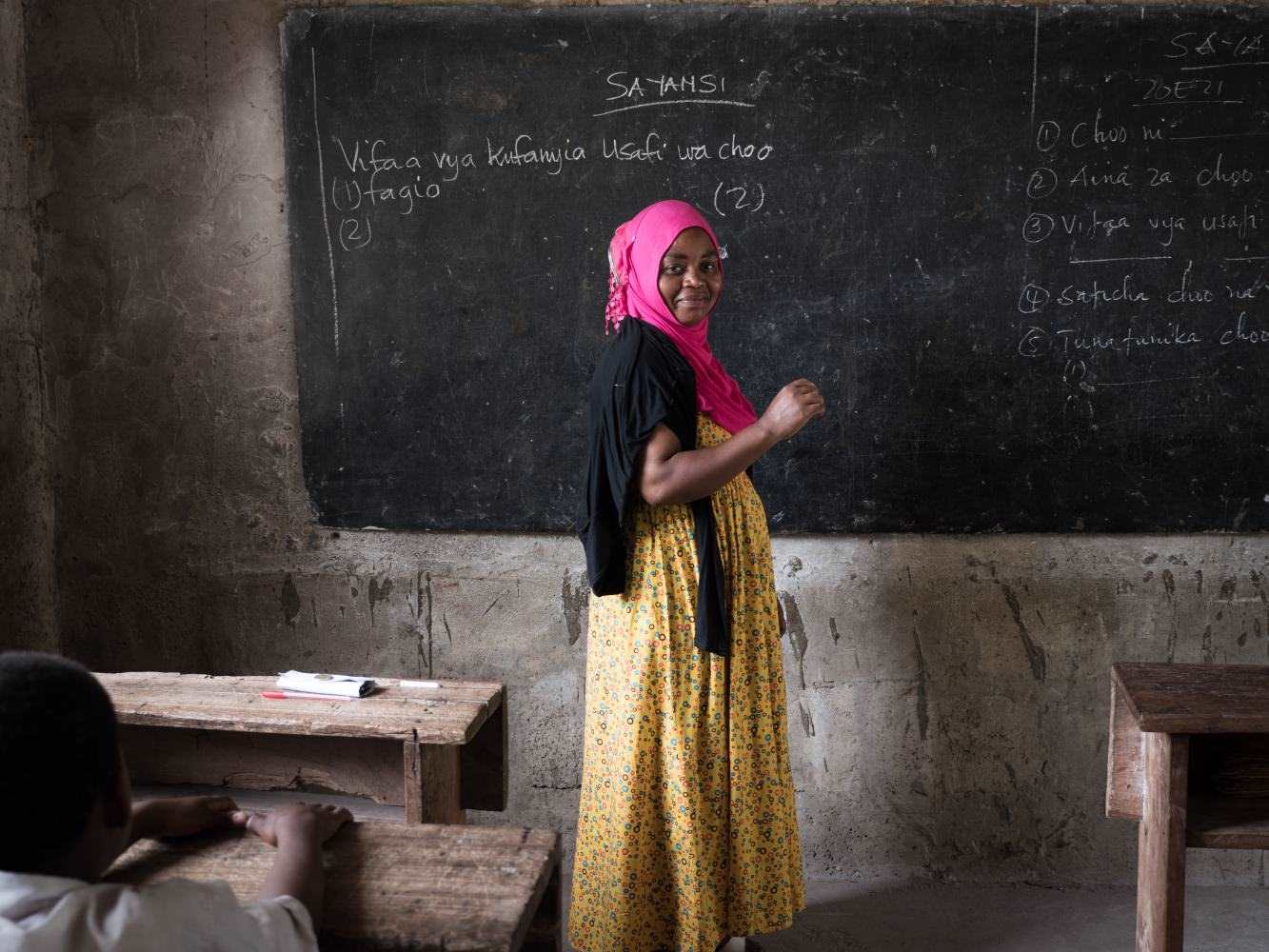

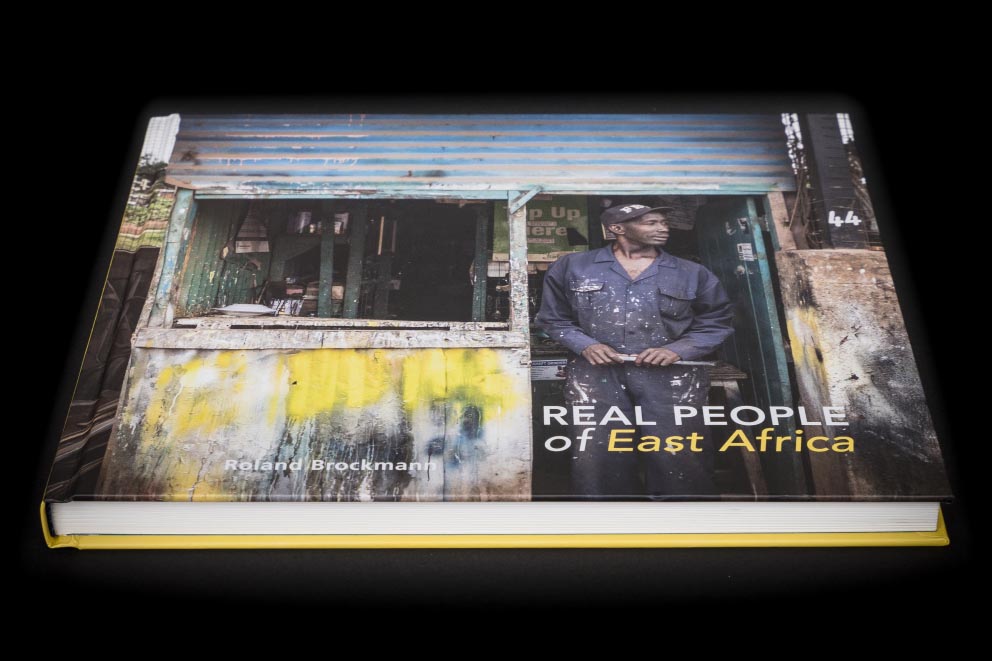

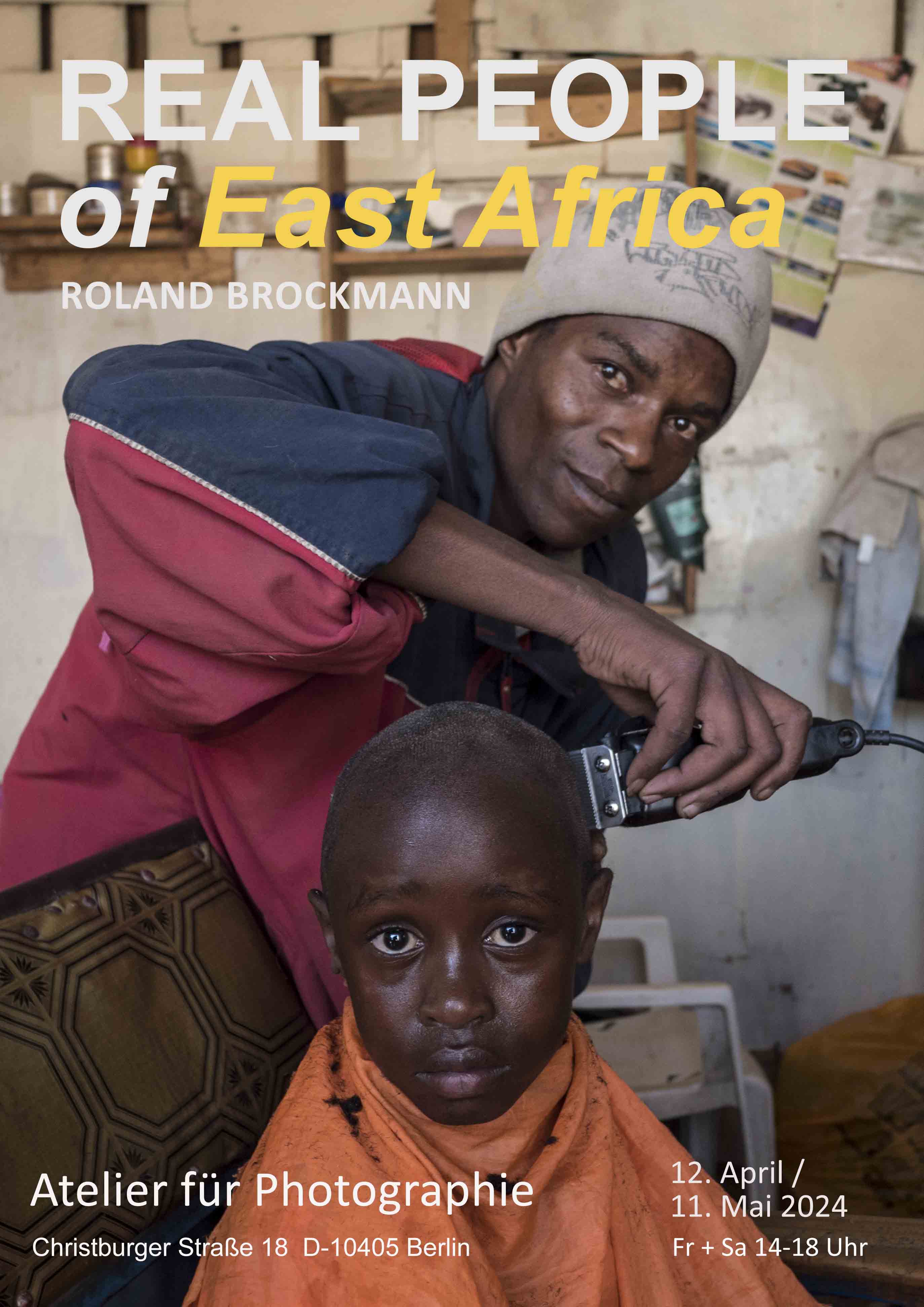

Dies ist kein Buch über Afrika, sondern über Menschen, denen ich dort begegnet bin – auf vier Reisen (2016 – 2017) durch Kenia und Tansania. Sie repräsentieren keinen Kontinent, sondern sich selbst. Sie erzählen von dem, was sie beschäftigt: Erfolg, Scheitern, Liebe, Trennung, Hoffnung, Alltag – den gemeinen Herausforderungen des Lebens. Und dies in ihren Worten. Ich habe dafür nur die Plattform gestellt, während sie mir die fotografische Bühne lieferten: ihre Kochstelle, ihre Werkstatt, ihre Wohnung, ihren Acker – also ihren Lebensmittelpunkt.

Selten habe ich mich so frei gefühlt, wie auf diesen vier Trips übers Land, mit Minibus, Motorradtaxi oder auch zu Fuß: Nicht etwas suchen zu müssen, sondern dem zu begegnen, was da ist, das war ein großartiges Abenteuer. Natürlich hatte auch ich bestimmte Bilder im Kopf, als ich mich aufmachte; doch die wurden durch die ersten Begegnungen bald beiseitegeschoben. An ihre Stelle traten Geschichten, weit persönlicher als ich selbst es erwartet hatte. Sie bilden sozusagen das Rückgrat dieses Buchs.

Es ging mir um Begegnungen auf Augenhöhe. Als Fotograf habe ich die Komposition der Bilder bestimmt, aber nichts arrangiert oder gar künstliches Licht eingesetzt. Beim Fotografieren bestand meine Arbeit vor allem im Fokussieren auf das Wesentliche.

Mit Glück sind so Porträts entstanden, die keine Umstände zeigen, sondern Menschen, die ihr Leben leben: Morgens aufstehen, Tee trinken, mit oder ohne Milch. Dem neuen Tag begegnen – so wie wir alle.

The Project

by Roland Brockmann

This is not a book about Africa, but about people I met there on four journeys (2016 – 2017) through Kenya and Tanzania. They do not represent a continent, but just themselves. They talk about what concerns them: success, failure, love, separation, hope, everyday life – the common challenges of life. And they do so in their own words. I just provided the platform, while they offered me the photographic stage: their fire place, their workshop, their apartment, their field – in other words, their centre of life.

I hardly ever felt as free as on those four trips over land by minibus, motorbike taxi or on foot. It was a great adventure not to search for something, but to discover what was already there. Of course, I also had certain images in mind when I started out, but they were soon pushed aside by the first encounters. Instead, other stories came up, far more personal ones than I had expected. They form the backbone of this book.

It was all about meeting people at eye level. As a photographer, I decided on the composition of the images, but didn‘t arrange anything and didn’t even use artificial light. When taking the pictures, my job was mainly to focus on the essentials.

With some luck, this resulted in portraits that show no circumstances, but people living their lives: getting up in the morning, drinking tea, with or without milk, and facing the new day – just like all of us.